Why employees leave

I was recently reading a post by a fellow contributor on LinkedIn about millennials’ frequent urge to change jobs. He wrote about people who had worked all their lives in one or two organizations and wondered if the reasons why millennials were into job hopping were due to a lack of challenges, appreciation, and increases in compensation. Being of the ‘old school’ and not believing that job-hopping leads to name, fame, and fulfillment, I gave in to the temptation to respond.

The first thing he wrote about was the absence of challenges. If people are not challenged and forced to move out of their comfort zone, they would soon tire of the mundane. Reading that, I wondered about the types of challenges encountered by people in our past who had truly left their comfort zones and brought about (or influenced) remarkable and long-lasting changes. For instance, I tried to imagine the challenges that Rembrandt or Michelangelo faced that forced them to create what are celebrated in awe centuries later and will (hopefully) continue to be for centuries to come

what made Ada, the Countess of Lovelace, and the Wright brothers think up such intense innovations without which life as we know it would not exist; what made Albert Einstein do his thought experiments and Srinivasan Ramanujan become intensely intimate with integers and discover the mysteries of science and mathematics which are still being worked on many decades after their passing.

What challenges did these incredible people, and many more such unnamed creators and innovators, face?

I declare that they did not face any challenges at all. At least not any that made them do what we remember them for. What made them do all that they did was the urge to question, their insatiable curiosity, and the desperate need to excel—the fire within. So also for many others who remain unnamed.

The romantic notion that a person needs challenges to inspire them to move out of their comfort zone, think out of the box, and shine like a diamond (crazy or otherwise!) is just that—a romantic notion. How could it be possible that a continuous stream of challenges coming at a person will encourage superlative response and performance? On the contrary, wouldn’t such a situation weigh down and make one weary?

Continuous challenges are what paramedic teams face, or firefighters, or soldiers on the battlefield. For these persons, it is what their profession demands or what nature has put their way. And surely, aren’t such challenges unwelcome?

No, dear readers. Challenges do not inspire. They do not make people think out of the box. They do not make people move out of their comfort zones. They do not encourage people to dedicate themselves to any particular employer. The only challenges that actually do inspire are those that are sparked by curiosity and the urge to excel. To the curious mind, everything can be interesting, inspiring, and a thrill. On the other hand, a regular stream of challenges that is not rooted in curiosity can be a burden on the mind and body and could ultimately become the reason for people leaving an organization.

The second point was about the lack of appreciation. I admit that I somewhat agree that appreciation is always a great inspirer and motivator. We all like to be appreciated—no exceptions. But only if the appreciation is for a significant achievement. Admiration is a double-edged sword that, if dispensed without adequate reason, will sound hollow and patronizing, particularly to the high performer. And it could very well end up producing a narcissist who constantly needs to hear applause for completing routine tasks. The other danger of constantly being appreciated is the possibility that the person may get labeled as different from others. It may identify one as being too different from the regulars and might make them stand too far out. And that could lead to major issues. Here, I feel that I must explain myself, so please bear with me.

Humans have a curious temperament. They need to be part of a group and, yet, at the same time, stand out and be different.

The need to be accepted as part of a group is a fundamental need that we all carry in our genes. It originates from the time when we came down from the trees and began competing for food and habitat with other predators such as lions, wild dogs, and other ferocious animals. The early humans did not have advanced weapons, which made it essential that in such hostile environments they worked as a team not only for a successful kill but also for survival. This enforced teamwork eventually led to the formation of ‘circles of trust,’ working together to achieve common objectives like hunting, migrating safely, setting up habitats, and generally looking out for one another. Indeed, their very survival depended on being accepted into a group. In today’s context, we see this team or group formation around work projects and other common interests.

At the other end of the spectrum is the need to be appreciated, to stand out, to be special. This is also an extremely basic human need. It boosts our self-esteem, our ego, and our sense of being important. It makes us feel valuable. This is easily signaled by giving special attention to a particular person or handing out doses of appreciation in various forms to the chosen one(s). But making a person stand out also isolates them from their group, team, or circle of trust. It may even lead to jealousy and resentment. And that could be fatal for the person’s identification with their group, their belongingness.

Which brings me back to the notion that appreciation is a double-edged sword to be used judiciously and with extreme caution.

The final point was about the lack of adequate revisions in compensation. On this, I can say with total honesty that I have yet to meet a person, man, woman, or child, who was satisfied with what they had. Be it house, car, toy, salary, office, jurisdiction, or how far they could throw a ball. The list goes on. It is never enough. Hence, regular increases in compensation also could not really be the reason why one would not change employers.

Ok, so that was about refuting my fellow contributor’s notion about what made people leave employers. Now a few words about what it is that make people stay.

The simple fact of the matter is that people will not leave if they are getting what they need. Not what they want, but what they need. So, for any employer to retain people, what is required is to find out what is needed. As simple as that. But then again, not quite that simple.

What does a person really need?

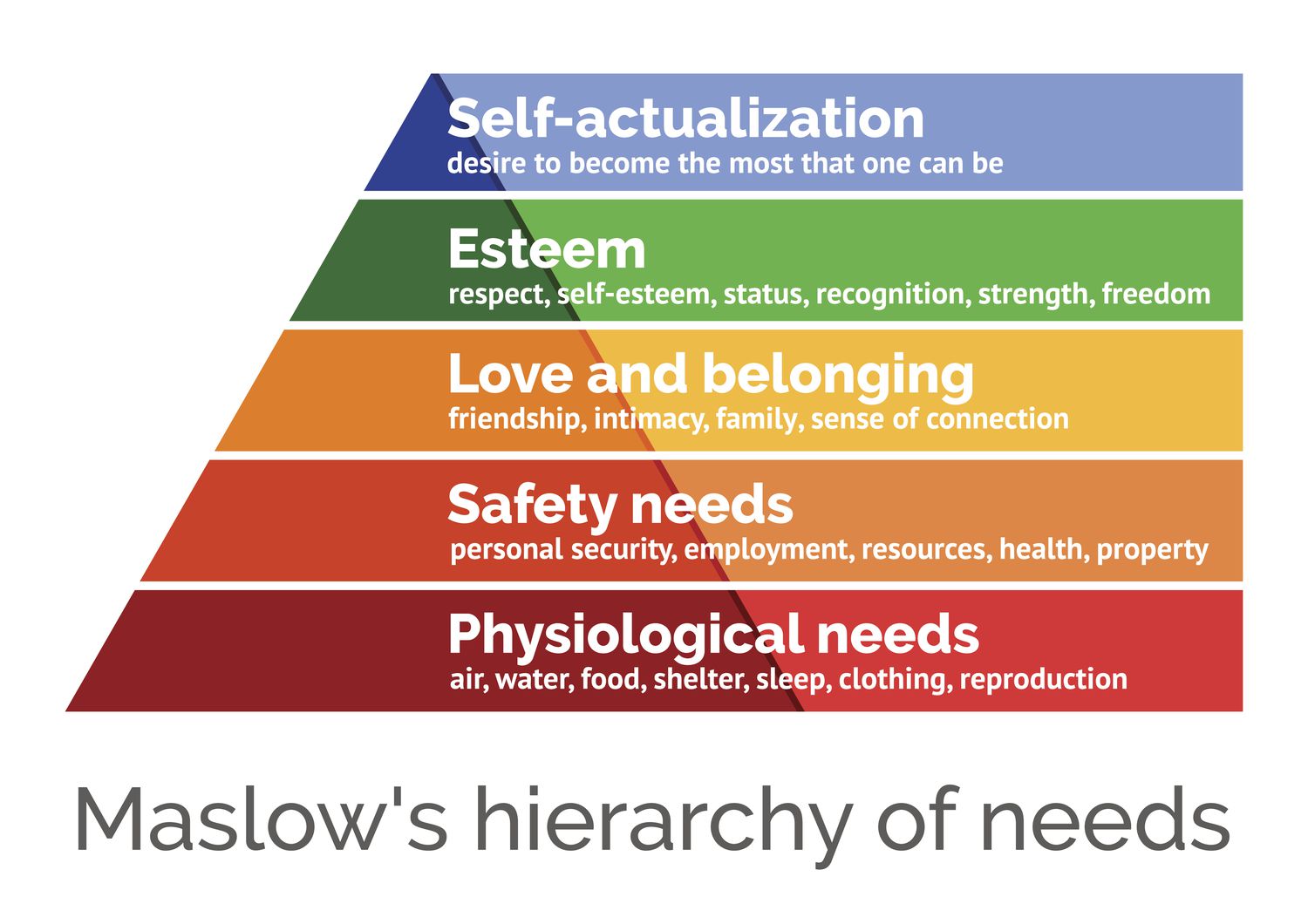

For the answer, I go to Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs, presented pictorially (see diagram) as a pyramid that shows the six essential needs of a person in decreasing order of necessity as we move up the pyramid. Bottom up, the needs are physiological, safety and security, acceptance and belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization.

The bottom two levels of physiological and safety needs are not relevant for this discussion. Any person who is working in an organization can be assumed to have a reasonably high level of fulfillment in these needs. That leaves the top three levels covering social, ego, and actualization needs.

The first of the upper three levels deals with the need of a person to belong, to be accepted, and to be connected (remember when we were talking about the need to be accepted as a part of a group as a fundamental need?). This would be the first need fulfillment that a person would seek, and if their working environment adequately provided this, there would not be any immediate or urgent compulsion to leave.

As an aside, if an organization wanted a person to leave, all it would need to do is to make that person feel unwelcome and unwanted—unaccepted.

After the need for belonging has been fulfilled, the next need that arises is the need for self-esteem, respect, being recognized for specific achievements, accorded a status, and provided a freedom to judge—the next level of the pyramid. It shows that people who have accepted him also believe in him. Here too, if a person is given responsibilities and the freedom to perform, there would be even lesser reason to quit.

The final level of need is to be able to be in competition with only one’s own self. Where one tries to grow beyond what one is today. This need is more of a self-fulfillment need than one that can be satisfied by an environment. However, if a person can find this in their place of work, there would be almost no reason why they would ever want to leave.

I conclude here by saying that if a person has been hopping through several jobs within the span of a few years, it is really because the needs of acceptance and esteem are not being fulfilled. The other side of this is that if an organization is not able to retain people, it should likewise look for indicators where Maslow’s need hierarchy is not being fulfilled.

Acknowledgements: Photographs from Unsplash by Anthony Fomin, Marc Weiland, Jon Tyson, and Andre Hunter

Further reading:

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal ISBN 0-07-043174-4; ISBN 0-385-33430-3